The Jendoul: toward the creation of an iconic Islamic Gondola

Our explorations of Iraq’s watercraft heritage began with the rural and the most ancient types of boats: those which could conceivably have formed part of a Mesopotamian Ark, such as the Guffa coracle, the Shasha reed bundle boat, and the Isbiya or Kaiya, a frame-built barge made from sticks and woven grasses. All these were made using locally sourced plant materials, without planked wood or the use of metal, with natural bitumen for waterproofing; they could have been made the same way since prehistory.

But we soon realised that boats of more recent origin and more sophisticated design were equally endangered. In 2018 we began our collaboration with the community of Huwair, once the boatbuilding centre for the Marshlands, where the memory of building Tarada and Meshouf canoes was still alive. These boats were made of planked wood that was often imported, and used plenty of nails; clearly this method of making them was not prehistoric (though boats of a similar form are depicted in Sumerian models). With their distinctive high curved prow, they were seen by locals as an art form and used by Sheikhs as a status symbol, and their aesthetic suggests a transition between rural boats and more self-consciously stylish urban ones.

In 2021 we began studying the maritime heritage of Basra, where again, traditional boats had almost completely disappeared from use. After commissioning a series of study models of different types of Ashari Balam – Basra’s equivalent to the Gondola, an elegant boat used on the city’s canals and on the Shatt al-Arab for local transport and leisure – we worked with local modelmaker and maritime historian Asaad Dawood and craftsmen to reconstruct and launch the first traditional Ashari Balam seen on Basra’s waters since the late 1990s.

These were steps in the direction of a far more challenging boat reconstruction: the Abbasid Jendoul, a boat at least eight centuries old, and the most “luxurious” we’ve yet studied.

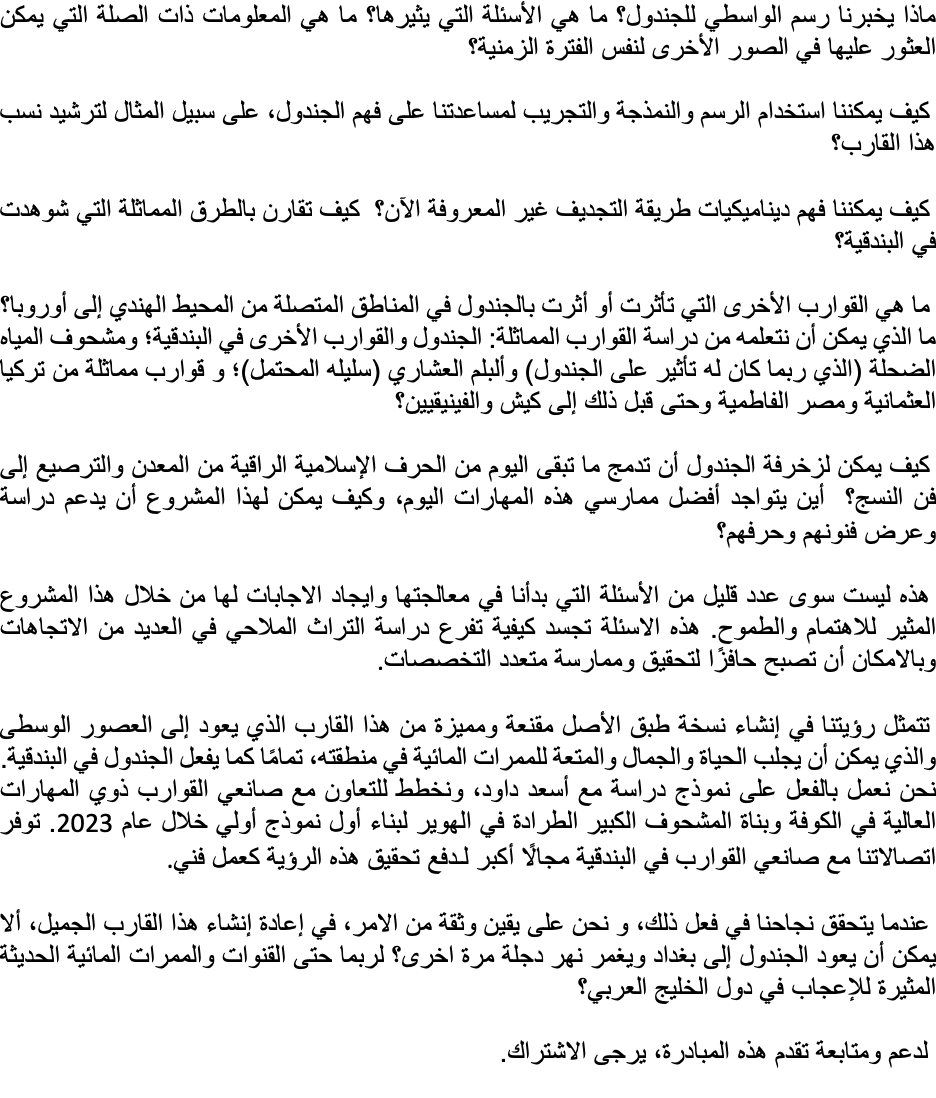

Rashad had become fascinated by the image of this vessel, depicted on the cover of Dionisius Agius’ book “Classic Ships of Islam”. The picture, by Yahya al-Wasiti from his 13th-century illustrations of the “Maqamat” of al-Hariri, shows a richly ornamented boat, comparable in form and style to the Venetian Gondola, but rowed (uniquely among the boats we’ve studied) by three men standing up. Clearly it was a river boat of some size and power, able to navigate against the strong currents of the Tigris.

Through engaging with the city of Venice during our participation in the Biennale Architettura 2021, we became more and more intrigued by the parallels between Venice and Basra as canal cities, and between their boats. We began to develop a plan to reconstruct the lost Abbasid Jendoul.

We knew our methodology would need to be different from previous workshops. Until now, we’ve only worked with boats where there is at least some living memory of how they were made, from elders who used to make them or have watched others do so. This one hasn’t been made for several centuries, so our approach has much in common with experimental archaeology.

What does al-Wasiti’s illustration of the Jendoul tell us? What questions does it raise? What relevant information can be found in other images of the same period?

How can we use drawing, modelling and experimentation to help us understand the Jendoul, for example to rationalise its proportions?

How can we understand the dynamics of this now unknown rowing method? How does it compare to similar methods seen in Venice?

What other boats have influenced or been influenced by the Jendoul, in connected regions from the Indian Ocean to Europe? What can we learn from studying comparable boats: the Gondola and other boats of Venice; the marsh Meshouf (perhaps an influence on the Jendoul) and the Ashari Balam (its possible “descendant”); similar boats from Ottoman Turkey and Fatimid Egypt and and even earlier to Kish and the Phoenicians?

How can the ornamentation of the Jendoul incorporate what remains today of Islamic fine crafts, from metalwork and inlay to textiles? Where are the finest practitioners of these skills found today, and how can this project support the study and showcasing of their arts and crafts?

These are just a few of the questions we are beginning to address through this intriguing and ambitious project. They exemplify how the study of maritime heritage branches out in so many directions and can become a catalyst for interdisciplinary enquiry.

Our vision is to create a convincing, iconic replica of this medieval boat that can bring life, beauty and pleasure to the waterways of its region, just as the Gondola does in Venice. We are already working on a study model with Asaad Dawood, and plan to collaborate with highly skilled boatbuilders in Kufa and the builders of the grand meshouf Tarada in Huwair to construct the first prototype during 2023. Our connections with boatbuilders in Venice offer further scope for advancing the realisation of this vision as a work of art.

If we are successful, as we are confident we shall be, in recreating this beautiful boat, could the Jendoul not return to Baghdad and grace the Tigris? Perhaps even the impressive modern-day canals and waterways of the Arab Gulf states?

To support and follow the progress of this initiative, please subscribe.